On Precedent: Learning from the Past Without Living in It

Every law student encounters the concept of precedent early on. It is the principle that decisions of the past inform the judgements of the present. Precedent gives structure to justice; it ensures that reason is not reinvented with every new case. Yet while precedent provides order to law, when applied unthinkingly to life, it can become a quiet form of imprisonment. We are meant to learn from what has been, not to live there.

The Burden Of Proof

One of the first lessons any law student learns is that claims require evidence. Assertions mean nothing without proof. The courtroom functions on this principle: the side that bears the burden of proof must substantiate its case beyond reasonable doubt. Yet outside the walls of the courtroom, most of us grant our own minds far too much leniency. We accept our excuses without cross-examination. We submit arguments for our limitations without requiring any evidence at all.

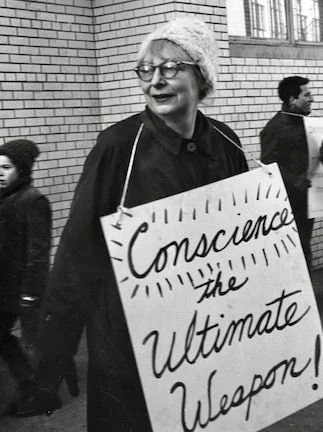

The Grace of Persuasion

Conflict reveals character more than agreement ever could. In law, this truth is self-evident. The art of advocacy demands precision, composure, and command of language. Yet in life, the same skills that win arguments can lose relationships. To argue like a lawyer and listen like a saint is to embody that rare equilibrium between assertiveness and humility. It is to understand that persuasion without empathy is dominance, and empathy without boundaries is self-betrayal.

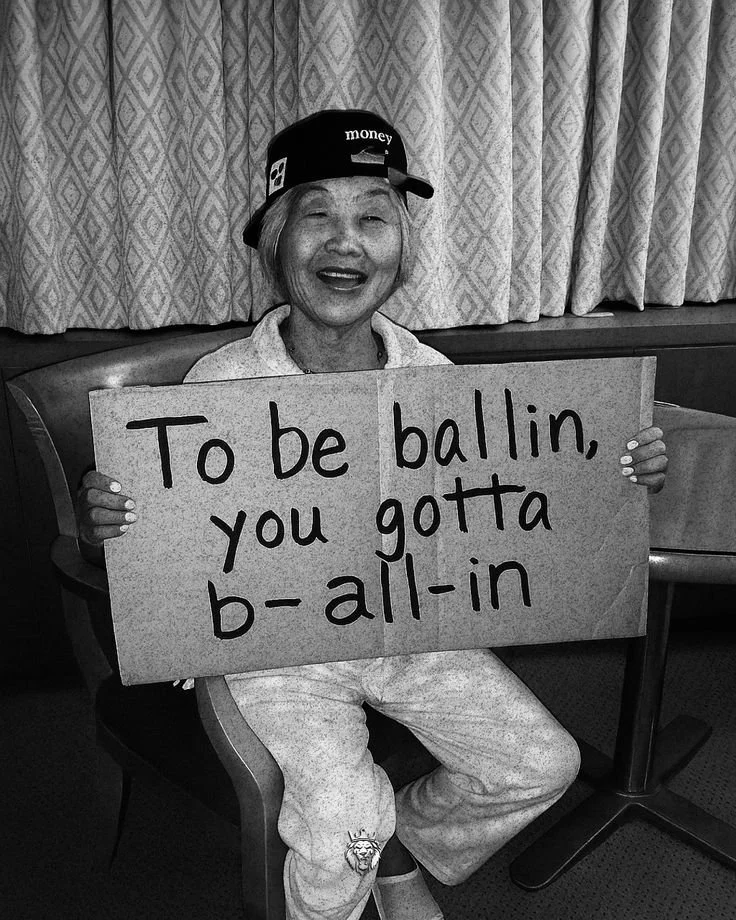

The Case For Delayed Gratification

When I began my studies, one of the most surprising lessons I learned was that patience is not passive. Whether in the quiet pages of philosophy or the practical world of human behaviour, I began to see that progress has its own pace, and that our task is not to rush it but to align ourselves with it. The mind that can delay gratification is a mind that has mastered itself. And in a world intoxicated by immediacy, mastery of self has become a rare and radical act.

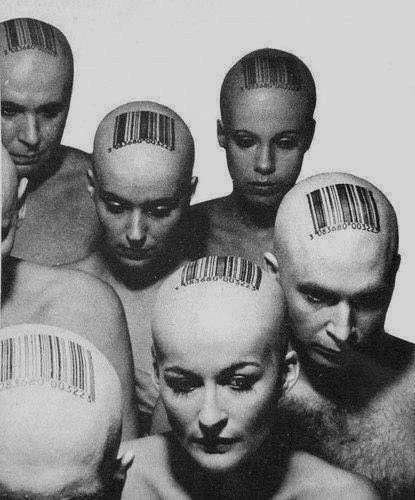

Order & Obedience

When I was younger, I believed freedom meant the absence of boundaries. I equated liberty with spontaneity, the ability to wake up and do whatever I pleased without schedules or obligations. Structure, I thought, was for the unimaginative: the meticulous, the boring, the predictable. Yet as I grew, through my legal studies and spiritual formation, I began to understand a truth that our culture fiercely resists: freedom without order is not freedom at all. It is chaos disguised as choice.